Archbishop Paglia at WISH Summit - Doha, Qatar, October 4 2022

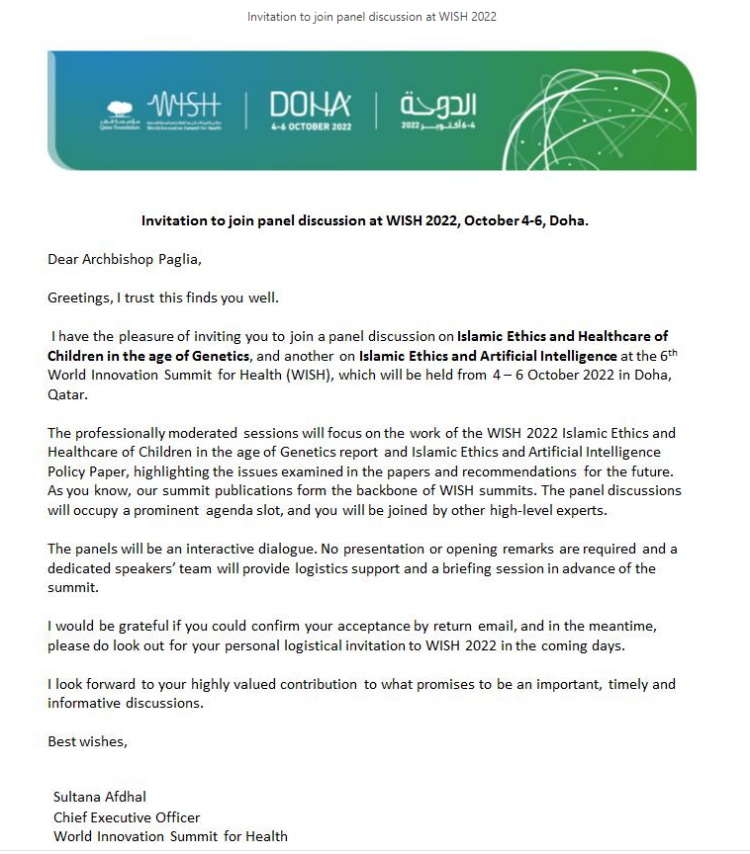

"I have the pleasure of inviting you to join a panel discussion on Islamic Ethics and Healthcare of Children in the age of Genetics, and another on Islamic Ethics and Artificial Intelligence at the 6th World Innovation Summit for Health (WISH), which will be held from 4 – 6 October 2022 in Doha, Qatar".

So has written Dr. Sultana Afdhal Chief Executive Officer World Innovation Summit for Health to Mons. Vincenzo Paglia, President of the Pontifical Academy for Life, inviting him.

On 4 October Mons. Vincenzo Paglia joined two panels.

The first, in the morning, on Islamic Ethics and Artificial Intelligence. Here his words:

Archbishop Paglia, in February 2020 you promoted the "Rome Call" in support of ethics in Artificial Intelligence - can you tell us briefly about this initiative?

With pleasure. The first signing of the Rome Call for AI Ethics in February 2020 was the result of a long series of reflections and discussions led by the Pontifical Academy for Life, the Vatican institution of which I am President. This document, signed by the Academy, Microsoft, IBM, the United Nations Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO) and the Italian government, outlines an ethical approach to artificial intelligence.

The idea behind this call – the urgency it expresses – is the need to ask those who conceive, develop, and adopt artificial intelligence to always put humankind and individual human dignity at the center of every project. We believe that AI is a powerful and valuable tool that must be, first, programmed, and then, used for the good of the whole of humanity, not merely for profit. Instead of the current algo-cracy, where algorithms decide what is right and appropriate, we want to institute an algo-ethics, a universal language based on shared values that respect the dignity of every human being.

The Rome Call is divided into three main parts:

ETHICS: All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights.

EDUCATION: Transforming the world through AI means undertaking to build a future for and with the younger generations.

RIGHTS: The development of AI in the service of humankind and of the planet must result in regulations and principles that protect people – particularly the weak and the underprivileged – and natural environments.

It also proposes six principles:

1. Transparency: in principle, AI systems must be explainable;

2. Inclusion: the needs of all human beings must be taken into consideration so that everyone can benefit, and all individuals can be offered the best possible conditions to express themselves and develop;

3. Accountability: those who design and deploy AI must proceed with accountability and transparency;

4. Impartiality: Exclude bias in the creation and use of AI, thus safeguarding fairness and human dignity;

5. Reliability: AI systems must be able to work reliably;

6. Security and privacy: AI systems must work safely and respect the privacy of users.

In these past two years, the Rome Call has been signed by additional stakeholders who belong to different sectors, cultures, and religions. The number of signatories, all of whom are committed to following the Call’s principles and to working for ethically sustainable AI, continues to grow. This leads us to appreciate that we have been able to understand and express the urgency that is driving not only the Western world but every part of the planet and a great number of actors. The Rome Call, born first as a document, now has a clear greater purpose—becoming a movement that has reached and motivated all of society.

On the specific topic of health:

In this Doha Conference, which is a key event on the global healthcare innovation horizon, we have seen and will still see extraordinary inventions that can help human beings in manifold circumstances.

Today we have heard how artificial intelligence systems, now and tomorrow, can lead to scarcely believable improvements in the medical arts. We should be both proud and grateful.

I encourage you to ensure that those who work in this field, which is so personal and delicate, will always give primary importance to humanity and to individual humans. For this, two things are needed:

First: Justice. It would be tragic if these complex and ultra-sophisticated systems were available only to the lucky few who can afford them. We must work to make it possible for each individual, and each disease, to receive the best possible treatment.

Second: Anthropology. Today's hyper-technological medicine runs an increasing risk of creating distance between doctor and patient. Technology inserts itself between the two, controlling, sometimes completely, their relationship.

As I said before, we have in mind an artificial intelligence that puts the human person at the center. In the health sector, this means both the AI that is centered on the patient, and the AI that is centered on the physician.

Let me point out an interesting biblical perspective. The Gospels, tell of a number of healings that Jesus worked, but with one exception, Jesus healed only those whom he could touch and see. He did not heal remotely. Like a good doctor, he wanted to see his patients personally.

Healing is a human thing. It comes out of a meeting between individuals and can’t be reduced to technology. Peoples’ bodies are not machines that are repaired mechanically. With that understanding, I hope that all the doctors present today will commit to using artificial intelligence in ways that strengthen their gifts of compassion.

The second panel was on Islamic Ethics and Healthcare of Children in the age of Genetics.

· Archbishop Paglia, what are some of the main ethical issues relating to genetic testing in children particularly from a Catholic Christian perspective?

Let me begin to talk about ethics by highlighting a cultural aspect that is often overlooked. It is clear that biotechnology offers significant opportunities. At the same time, however it tends to consider the person in a simplified fashion in order to make him or her more easily analyzable, controllable and useful in a given context. This goes not only for children, but for the entire spectrum of living beings (and not only humans). Our responsibility in this area covers not only what we know (through scientific research) and what we do with our knowledge, but also how we know.

Trying to correct malfunctions or even to improve performance leads to living beings becoming “machines” that are as productive as possible. This is a utility-based approach, which quickly risks becoming prey to economics. For this reason, we have to be careful that the adoption of genetic diagnostics (and therapy) does not lead to a reductive vision of the human person. The life and health of a person is certainly influenced by his or her genetic structure, but the person is not just genes. [i] Epigenetics[ii] tells us that the expression of a person’s genetic makeup is the result of the interaction among different factors. The interweaving of innate and acquired elements (nature and nurture) is particularly relevant with regard to complex personality characteristics, such as a person’s intellectual quotient. [iii] Moreover, the technological resources now available to medicine have radically altered the way we consider the transmission of life, generation and filiation.[iv]

My references to genetics, epigenetics, medicine and the parent-child relationship (especially the mother), help us understand that we cannot ignore the overall context – which is biomedical, socio-economic and cultural – if we want to understand the full meaning of the biotechnologies that genetic engineering offers. The transmission of human life is not simply a biological fact nor is the patrimony that is transmitted simply genetic. Together they provide us with the meaning of existence and the way in which cultures and religions understand it. We see in the attitude we have toward the generation and acceptance of children, in our entire relationship with life and, more generally, with the future, not only as concerns the parents, but also the whole of society. Having children is not the only form of fertility. Fruitfulness implies a wider openness and commitment to life, especially as concerns the most helpless among us.

A new and disruptive factor that we see is the progressive blurring of the line between diagnosis and screening. While diagnosis focuses on finding specific diseases in individuals with heightened risk profiles, “screening” is used on larger groups, analyzing ever larger segments of the genome. The information collected makes it possible to identify and eliminate genetic variants that are considered disadvantageous, even if it is not clear that they can actually be considered pathological. This results in a sort of preventive eugenics, similar to instances seen in the past.

To understand this new factor, we need be clear about a number of things: the individual’s biological data, the healthcare services that a sick person can access, and a more generalized understanding of genetics in the overall vision of the human person and of the societal grouping to which the person belongs. The perfection-oriented approach (with inevitable control and conformity) that is reflected in this new factor risks inducing an erroneous conception of the human condition, as if one could eliminate the limitation, the “imperfection.” the vulnerability that is intrinsic to the human condition and that makes mutual care and protection necessary.

It is against this background that we have to evaluate genetic diagnosis: the costs and benefits for individual and public health, the methods of managing information, and respect for the autonomy of patients (proportionate to age and family situations).

In the Christian perspective, therefore, nature is entrusted to man who is free to intervene, but only according to criteria that respect the dignity of the person and the right to life, in an atmosphere of acceptance and care for all involved.

· From a Christian ethical perspective, is it legitimate to abort an embryo or fetus with a genetic disorder? If so, in what cases?

In the Catholic perspective, life is a fundamental value from its beginning and can never be unjustly ended. Therefore, the only case in which the ending of the life of an unborn person can be considered licit is the very difficult situation where there must be a choice between the life of the mother and the life of the unborn person she is carrying (“vital conflict”). This does not mean, however, that all available therapeutic means are always to be used to prolong life. Even in perinatal situations, the criterion according to which to proceed is proportionality, which allows the suspension of treatment when adequate proportionality is lacking.

· What do you think about genetic testing of children for adult-onset disorders for which there are no available interventions during childhood? What are the ethical issues of concern there?

There is no opposition in principle to the genetic search for factors that predispose an individual to increased risk of a certain disease. The ultimate goal, for the adult, is to put in place a series of measures to prevent or delay it. In addition, testing can lead in general to earlier development of appropriate therapeutics.

The ethical problems involved concern;

- The fact that predictions with respect to timing and severity are uncertain and can lead to speculative over-medication of society.

- Possible psychological negativities, social and workplace discrimination, insurance price increases, etc.

- Difficulties in ensuring equity in access to medical care.

- The management of genetic information and issues of informed consent, privacy and confidentiality

- In children, issues surrounding their ability to give informed consent.

In any case, in principle, predictive medicine can have decidedly positive effects in the lives of patients. Its frequency depends on the availability of effective techniques, its ethical, social and legal implications, the adequate training of doctors, ethics committees, health professionals, citizens and patients, their proxies-particularly families, when patients cannot give consent. All this requires further study and reflection in the years to come.